How the Fed and Quantitative Tightening Affects Stocks

Updated on October 25th, 2023

It’s a myth that commercial banks can create an unlimited amount of money out of thin air. It is the Federal Reserve that ultimately controls the money supply and they use banks to do their bidding.

We discuss how that is done, the implications of such mechanisms on asset bubbles and inflation, and why you should be aware of this information given that the Federal Reserve has entered a historic rate increase cycle with intentions for balance sheet reduction. Last year I wrote about why the stock market bubble would pop, and we have now reached that juncture because all the excess liquidity that was injected is now being reversed. Although its acting more so like a slow deflation instead of a rapid pin prick.

Do You Know The Banking Business Model?

For starters, some sciolists like to pretend that they are in a club that has secret knowledge about the banking system and that what everyone else believes about the banking business model is a lie. They say that banks don’t actually take customer deposits and also don’t actually lend out money.

Surely that sounds ridiculous to anyone who has a bank account or has ever had an auto loan, credit card or mortgage. It would make one wonder what the point of all those bank branches were for if that were true.

This flawed premise is usually used in the context of cryptocurrencies to confuse and obfuscate underlying mechanics of money and try to legitimize scams like Hex crypto by claiming they work “just like the banking system,” when they really don’t.

The Source of the Conspiracy

These viewpoints generally stem from misreadings of quotes taken from various sources such as statements made by economist Richard Werner, who said “The legal reality is banks don’t take deposits, and banks don’t lend money.”

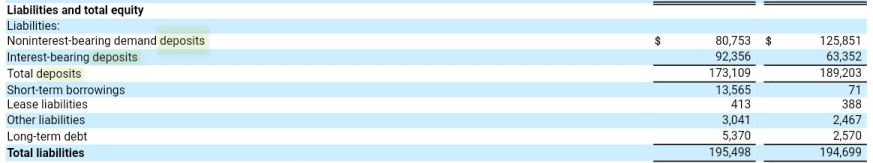

This must be news to every bank that lists deposits and loans on their balance sheets:

Of course, if one bothers to read beyond just that cherry-picked quote, a few sentences later he states “If you give your money to a bank, even though it’s called the deposit, this money is simply a loan to the bank…. Banks borrow from the public. That much we’ve established.”

Okay, do you feel any different about the perspective that when you give money to a bank, it is actually a loan to the bank and not a ‘deposit?’ It’s trivial semantics from an ivory tower professor.

The viewpoint is further muddied for some people by a handful of academic papers, such as those from the Bank of England (2014) and S&P (2013), that take a somewhat pedantical distinction about the chicken or egg of money creation, whether it starts first with deposits to make loans or that loans make deposits. In the circle of life for banking where loans become deposits somewhere, it’s not particularly important to understand that the aggregate banking sector expands the money supply when they lend. Nobody disputes this; it’s been a function of banking since the beginning.

The Commercial Banking Model

Let’s start with the commercial banking model. It’s very simple. They take cheap money and loan it out for a higher interest rate, capturing the spread between the two rates. The most familiar type of cheap funding is customer deposits.

Why do banks want customer deposits? It is because it’s their cheapest source of funding. The largest banks like Bank of America and JP Morgan pay about 0.01% per year for the privilege of holding onto your money and then loan a portion of it out for profit. The rates they earn from credit card loans, mortgages, and personal loans are all around 3-18%. Therefore, barring any risk considerations in normal economic times, it is in their interest (pardon the pun!) to attract as much customer money as possible to maximize cheap funding that they can turn around and loan out.

Commercial banks also earn a decent portion of their earnings from customer fees, such as overdrafts, late payments, ATMs, and loan originations.

The Bank Balance Sheet

When a customer deposits funds into a bank, the money is added to reserves on the asset side of the balance sheet and the IOU is added to the liabilities side, and the statement balances, hence the name.

Bank reserves are made up of customer deposits, proceeds from long-term debt, proceeds of assets they’ve sold, and some of the reserves may be made up from interbank lending. Occasionally money is borrowed directly from the Federal Reserve itself via the discount window to top up the reserves, but the lender of last resort is only utilized during periods of extreme market stress. We’ll talk about the impacts of quantitative easing in a later section.

Banks usually hold additional assets on their balance sheet other than customer deposits and physical currency and include loans they have not repackaged and sold off (discussed later), investments in government debt, equity in investments and intangibles.

Loans are bank assets and go on the asset side of the balance sheet, which brings us to the discussion about how money expands with commercial banking.

Expansion Of The Money Supply

When a bank takes some of its reserves and sends them out to be deposited in another bank, the receiving bank adds the money to their assets along with a matching deposit liability from the customer who brought it there. The bank’s balance sheet balances.

All the depositors at the sending institution show their original bank account balances, and the receiving bank receives new funds on the deposit. Thus, the money supply in the economy has artificially expanded since the total dollars in both banks electronic ledgers is greater after the loan is deposited by the receiver. This only becomes a problem if all the depositors in the first bank want their money back at the same time, known as a bank run, and there isn’t enough physical currency and reserves to cover the demand.

Wide scale bank runs have not been a major problem with commercial banks since the FDIC and European equivalents were formed to guarantee deposit balances, but they do happen occasionally sometimes related to political events. SVB and First Republic did experience bank runs in 2023 because they catered to wealthy individuals and businesses and had large balances of uninsured deposits. Also, there have been several cases of bank runs on cryptocurrencies since these are not regulated entities and insurance is not widely available to backstop losses.

The key point to realize is that for every loan created, a matching customer deposit is created somewhere in the banking system (unless the receiver of the loan takes the money out in physical currency, that is). When a loan is approved, the loan amount is added that banks asset side of the balance sheet and a matching loan amount is added temporarily on the liabilities side until the funds are dispersed to the other bank.

If the receiving bank is the same bank as the lending bank, the asset and liability end up on the same balance sheet with matching values. This is what it means when the academic papers listed above say that a loan is added to both sides of a balance sheet, but it is really only true when both sides of the transaction occur at the same bank.

The academic papers generally consider the banking sector in aggregate, since the economy is interconnected and banks are constantly shifting money around amongst each other.

This is an important point that the economic dilettantes miss when interpreting the “both sides of the balance sheet” commentary. They try to make this sound like it’s some kind of conspiracy, when in reality, it’s just simple accounting. They misinterpret this to mean that banks can create unlimited amounts of money in the economy, which is flatly false. Banks are subject to economic capital requirements and stress testing exercises which limits their ability to leverage up their balance sheets. You have to remember that banks are still businesses and they aren’t able to take unlimited risks if they want to remain in business. A certain percentage of loans go unpaid and are charged off with losses.

It’s also important to point out that this is not a new concept. Banks have artificially expanded the money supply since they were invented. The impact on the money supply from commercial banks will reach a steady state at any point in time that balances risk and reward in the economy given its current environment. It’s not like banks are running “printing presses” in their basements and dispersing the funds continuously. Sometimes they expand and sometimes they contract, but it only becomes long term inflationary if a bank failure causes the government to come in an pick up the tab and indemnify losses.

Reserve Money Multiplier

In the typical economics textbook, the concept of money multiplier is used. Banks in the US used to be required to hold 10% of the money they received from depositors and could loan out the rest. The geometric power series relationship of this arrangement meant that in the aggregate banking system, as much as 10 times the deposit would emerge in the economy. However, the reserve requirements had been non-binding for decades and the Federal Reserve dropped it to zero in 2020.

This is one of the reasons why the “money creation multiplier” concept is not longer valid because it is no longer even defined with the division by zero. The economic capital requirements are similar, but each bank’s risk profile is considered for their required reserves.

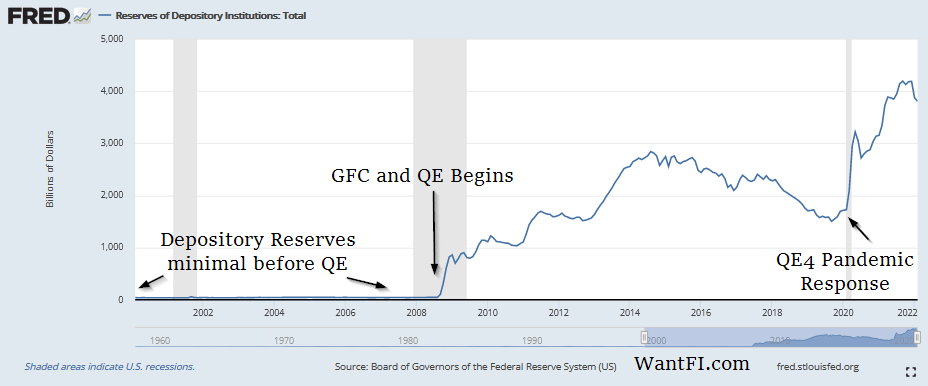

The second reason why it’s no longer accurate is because in the reserve money multiplier framework, the bank is implicitly limited by how many deposits it can attract. In reality, not only can banks can borrow reserves from other banks to make up the shortfall for short periods of time, the quantitative easing by the Federal Reserve has flooded banks with excess reserves. Banks rarely need to borrow from each other at all these days.

Modern Banking In the Age Of Quantitative Easing

We explain why Federal Reserve quantitative easing has flooded banks with capital, but first need to discuss mortgage backed securities since a big portion of that capital injection has come through those.

PRO-TIP: I rolled over a 401k into an IRA, and Capitalize‘s FREE service couldn’t have made it any easier to do. They work with all the major brokerages and handle the paperwork for you.

Mortgage Backed Securities

Before the advent of mortgage backed securities (MBS), the basic banking business model was for banks to collect deposits and then turn around and make loans and hold them on their balance sheets until maturity.

Mortgage backed securities (we will skip the tranche innovations from the discussion here to keep things simple) provided the opportunity to expand lending by packaging up all the various mortgages on the bank’s balance sheet into a pool and sell them off as a single diversified security to retail or institutional investors hungry for yield. This freed up the amount of money that banks could then turn around and create more loans for and earn origination and servicing fees on. Banks became a conveyor belt for mortgage originations.

Securitization by itself does not expand the money supply because the institutional deposits that are buying them cross over the balance sheet and net out.

However, one implication was that the default risk was transferred from the banks to investors. MBS became such great business that banks were running out of quality loans to originate and realized they could harvest and package up lower quality loans since they weren’t bearing the default risk. It got to the point where banks were underwriting “NINJA” loans: No Income, No Job or Assets. We all know how that turned out in 2008. The Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 changed a lot of the rules and set up basic minimum lending standards on qualified mortgages and required some “skin-in-the-game” on the underwriting.

What is Quantitative Easing?

Around the same time in the depths of the recession, the Federal Reserve started the grand experiment called Quantitative Easing in the US. So what’s Quantitative Easing? How does quantitative easing work?

Prior to QE, most of what the Federal Reserve did was manage the short term interest rates on interbank lending and the discount window. These short term rates would influence other interest rates in the economy such as customer deposits, the prime rate, and they would indirectly filter out to longer term rates through market participant actions. The concept is simple, lower interest rates lead to growth while higher interest rates slow down the economy.

The problem is this simple model is that once the central bank reduces short term interest rates to near zero like they did during the GFC, there is a wall that limits what they can do from there. What difference is it to a market participant to pay 0.25% or 0.50% on a loan? It’s basically immaterial.

Economics books used to be written with the concept that it was impossible to have negative nominal interest rates. The thinking was who would pay more for the privilege of having less money later if rates were negative when they could just withdrawal all their money into physical currency and stick it under a mattress? Denmark, in 2012, was the first to breach that negative rate threshold and the EU followed suit a couple of years later.

The United States took a different approach (which European Central Banks later copied) and started to manipulate longer term rates by buying assets with longer duration maturities from primary dealers (large banks that deal directly with the Fed). Quantitative Easing is using the Federal Reserve balance sheet to buy longer dated Treasuries and MBS.

Why? The point here was to manipulate longer term interest rates to a lower level to stimulate the economy. Longer term interest rates affect mortgages, business loans and corporates bonds. When something is cheaper, you get more of it.

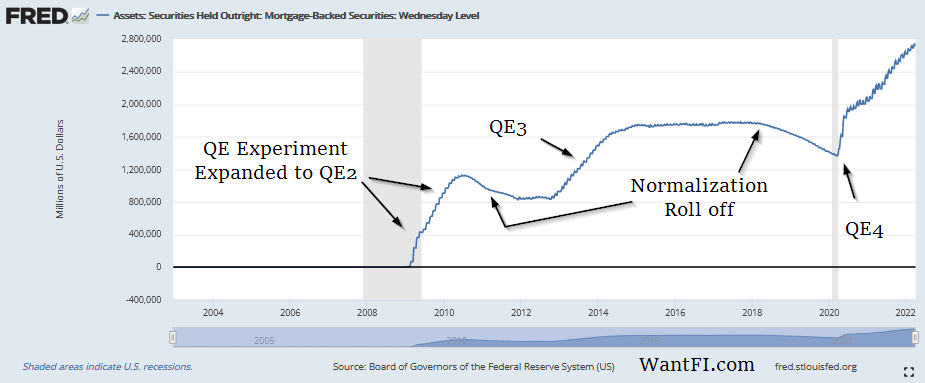

You can see in the chart below the quantity of MBS the Federal Reserve has bought since inception.

Money creation occurs when the Federal Reserve gets involved.

Federal Reserve Quantitative Easing Money Creation Explained

Selling assets to the Federal Reserve increases the money supply because the Fed just electronically prints the cash and adds the cash to the bank’s reserve account. With extra cash on the balance sheet, banks have more incentive to lend and stimulate the economy, or as the theory goes.

Of course, this is a joint decision with businesses and households who still remember the pain felt during the GFC recession. Households have not overleveraged themselves like they have in the past.

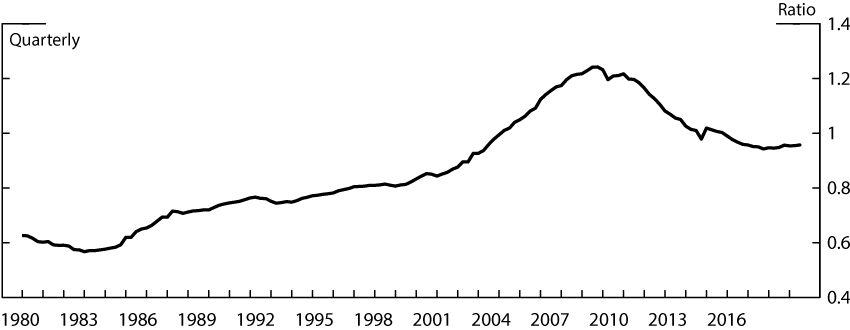

Banks are so flush with cash right now that they really don’t have enough places to put it. The loan-to-deposit ratio is the lowest level on record. This is another reason why the money multiplier doesn’t hold because banks have excessive reserves that don’t resemble anything like a reserve money multiplier.

Fed Quantitative Easing Implications

Financial crises always start with market participants seeking out riskier sources of return. This time the Federal Reserve was forcing investors and businesses to seek out riskier options in order to keep up with inflation because bonds were not doing it with the paltry yields. They called it TINA, “There is No Alternative.”

Asset Bubbles

Quantitative easing lowers the natural interest rate that investors would earn in a normal interest rate environment, therefore, there is less demand for bond securities. This has two complementary actions that causes asset prices to rise: not only do retail and institutional investors have to buy riskier assets to earn a real return on their money using assets like real estate, the stock market and art, but also since cheaper loans become more affordable, so you get more of them, which leads to asset prices being bid up all around.

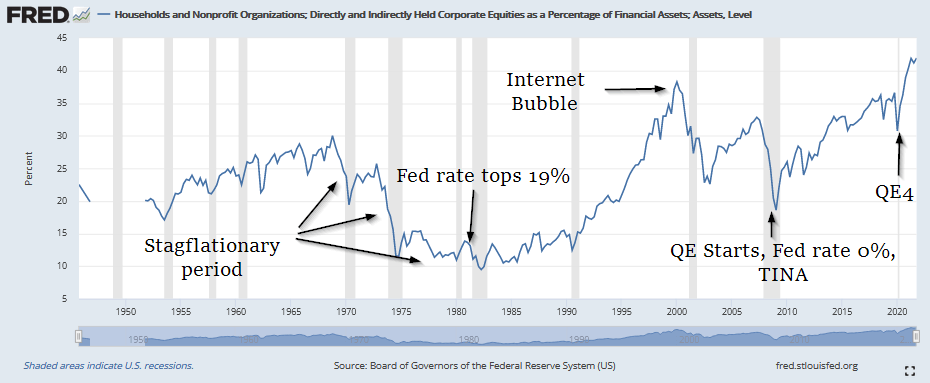

Not surprisingly with bonds paying paltry rates, investors in aggregate have allocated a larger percentage of their capital to the stock market, as shown below:

It becomes a bubble when the asset prices are so far from fundamentals that it becomes unsustainable and something comes along to prick the bubble.

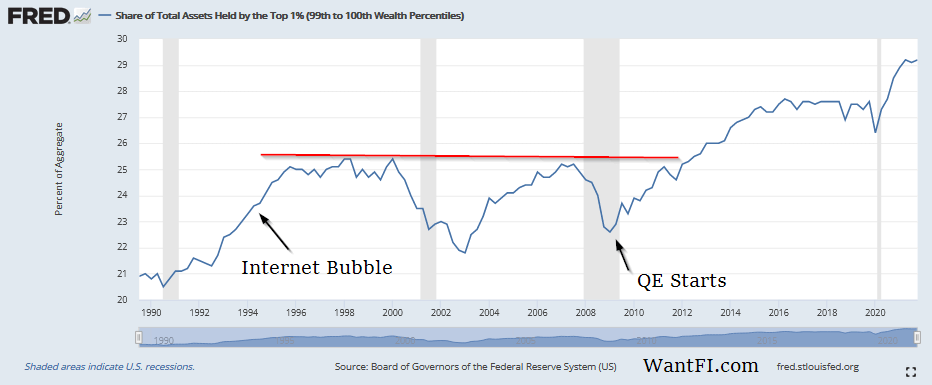

Also concerning is that as with every government action, there are winners and losers which has a moral dilemma of fairness. Savers are punished and debtors are rewarded. Retirees are forced to risk higher portions of their portfolios to volatile riskier assets otherwise they risk running out of money. First time home buyers end up paying a higher price for houses because investors have bid them up on their quest for better investments. Inequality expands since asset owners grow their assets at a higher rate.

Companies borrowed at ultra cheap rates and used the proceeds to buy back stock, increasing the valuation of executive bonuses and option compensation.

Is Quantitative Easing in the US Inflationary?

The way that the government defines the consumer price index (CPI) inflation largely ignores the effects of capital assets like the stock market and real estate and instead focuses on a basket of goods that households buy regularly, so the asset bubble that has formed has largely not shown up in these statistics.

Even still, the consumer goods basket inflation has been muted for the first 12 years of Fed QE and it has only reared its ugly head in 2021 and 2022. The Fed themselves have even been boggled by this conundrum and often attribute it to cheap labor from globalization and economic capital technology. The Federal reserve has injected trillions into the economy but the velocity of money has plummeted at the same time, which has also muted inflation. However, with the QE4 money bomb creating a third of all dollars in existence in 2020-2021, and the trillions of dollars in government stimulus, it was obvious to me that inflation would have to materialize at some point.

Our economy does not live in a vacuum and its hard to detangle the competing inflationary effects of both stimulus forces, but I want to make an important observation here. Federal Reserve QE is not the equivalent of “helicopter money” when the government just prints more money and distributes it to the population indiscriminately like they did with stimulus checks. That kind of action just permanently debases the currency and ends up with no benefit to the population because prices just rise accordingly.

Prices balance the scarcity of goods so adding an extra $5,000 to every household’s income doesn’t make scarce resources any more plentiful. From an Econ 101 standpoint, the demand curve shifts to the right, so prices rise. Furthermore, there is no mechanism to remove that type of cash injection. It’s not a loan.

In contrast, treasuries and MBS are loan securities which are eventually paid back to the bond holder. So barring any defaults in the MBS that the Federal Reserve holds, if they stop buying assets, eventually all their liquidity injection will be removed from the economy. Albeit, it could take decades to unwind if they don’t actively sell them back given the long duration nature of mortgages.

Quantitative Easing has an inflationary effect when it is put into the system and a deflationary impact once removed, so overall the long term net effect on inflation will be zero once the balance sheet is normalized (unwound). In fact, with interest being paid to the Treasury over decades on the underlying mortgages, it could have a deflationary effect if the balance sheet is ever completely unwound (which probably won’t happen in our lifetime, to be honest).

There have been 4 distinct QE injections since they started in 2008. Prior to the pandemic, the bonds were actually starting to roll off, but then the Federal Reserve went overboard to overcompensate for the government induced economic shutdowns to control the pandemic.

The ultimate question is will the Federal Reserve balance sheet continue to grow over time just like the national debt has done? If so, you can count on that having a permanent inflationary effect.

On the bright side, funds injected by the Federal Reserve are not needed for general government funding and is not subject to congressional oversight, so we have some faith that eventually the Federal Reserve balance sheet will be unwound at least somewhat. It could just take a couple of decades unfortunately.

How Does Quantitative Tightening Affect the Stock Market?

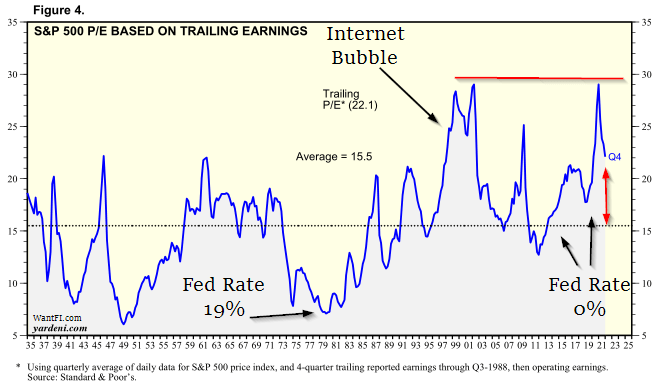

The common refrain of TINA, there is no alternative, is no longer applicable. Bond rates yield more than 3.5% across the long term spectrum and that is enough for pension funds and retirees to plan out their schedule.

As a result, the stock market will not have the same indiscriminate buying that it had before when quantitative easing drove down rates. Furthermore, as the Federal Reserve tapering leads to higher rates, more selling from the stock market should materialize until an equilibrium is reached that makes the equity risk premium attractive again.

Historically the only way to cleanse the system was through either a rapid devaluation of asset prices such as occurred in 1929, 1987 or 2008, or a long drawn out period where inflation adjusted asset prices don’t make a new high for many years including periods 1967-1991 and 2000-2008, or from 1987 until today for Japan. We don’t know how this will play out, but the valuation of the stock market was at peak bubble levels at the end of the year.

Implications

- It’s a good time to think about rebalancing your portfolio.

- It’s always prudent to invest in some real assets whose value proposition doesn’t require an ever expanding set of buyers to maintain its price and are not grossly overvalued, such as energy MLPs.

- Since we are in the midst of stagflation, it’s also smart to think about inflation hedged investments.

Come join the telegram chatroom for some more investing discussion.

Free Investing Tools

- Have Capitalize handle the paperwork for your 401K rollover to any brokerage, for FREE!

- Where does your money go each month? Track all your accounts and see if you are on track to retirement with Empower, for FREE! I use it myself to monitor my mom’s accounts to make sure she isn’t falling for scams or being defrauded.