Unpopular Opinion: Why The Roth Is Worse Than Tax-Deferred

Updated on December 5th, 2024

Note: I plan to update this article for the 2025 tax rates soon….

Retirement planning does not come easy for most people and there are a plethora of choices to make in the process.

This article is not about discussing whether you should pick an Individual Retirement Account (IRA) versus a 401(k), but instead it’s about whether you should pick the Roth IRA / 401k or the traditional account type.

This is a complex decision that involves a lot of factors, but at the end of the article you will be armed with the relevant information to make it.

The thing you are probably most interested in: Which account style leads to more money?

We will show with examples that for most people, the traditional IRA or 401k is better than the Roth, contrary to popular opinion and finance gurus who just assume the Roth is better without running any numbers.

What Is The Difference Between a Roth and Traditional IRA / 401k?

For a quick recap on the difference between the two, it comes down to when you pay the taxes. Yes, Uncle Sam always gets his cut eventually. Your options are to either choose a Roth, where you pay taxes upfront, or a traditional account where you pay taxes later. In retirement, the Roth accounts pay no taxes on distributions, while the traditional accounts pay ordinary income taxes.

The Roth variation has only existed since 1997.

Why Is The Traditional IRA Better Than The Roth? Tax Arbitrage

Almost all the personal finance gurus out there favor the Roth account type and tout the benefits of having tax-free income in retirement after decades of compounding. But there is nothing magical about paying taxes upfront that somehow leads to more money in the future. In fact, quite the opposite.

I go against the herd and explain why most people should skip the Roth option and pick the traditional type because, for most people, it will lead to more money. This is explained through the concept of tax arbitrage.

The fundamental idea is whether you pay taxes now or pay taxes later.

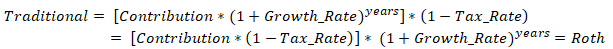

Mathematically, if the tax rate is the same in the contribution period and the withdrawal period, the after-tax value of both account types will be exactly the same from the commutative property of multiplication:

When is the Traditional IRA / 401k Better Than the Roth?

When your retirement tax rate is lower than your contribution rate.

This is the concept of tax arbitrage: You contribute during your peak earning years, taking a higher income tax rate deduction (saving more tax dollars now) and take distributions during retirement paying a lower income tax rate.

How Tax Arbitrage Works

If you wonder why your tax rate will be lower during retirement, it’s because when you contribute to a traditional retirement account during your working years, the deduction is applied against a single bracket, your highest marginal tax bracket, but when you take a distribution during retirement, your money is spread out over several lower tax brackets, each bucket being filled with a higher tax rate along the way, creating a lower average (effective) tax rate.

The valuation formulas become:

Since Retire_Avg_Rate <= Marginal_Rate, mathematically the value of the traditional account will be greater than or equal to the Roth account type. The worst case scenario is that the accounts have the same after-tax value if you are in the lowest tax bracket in both the working and retirement periods.

Of course, by retirement, the assumption is that you are actually retired. If you continue working while taking distributions from your retirement accounts, your regular working income will push up your marginal tax rate reducing the tax arbitrage benefit being described.

The only way the Roth could have more after-tax value is if your average retirement tax rate is higher than your marginal tax rate during your working years, such as if future tax rates increase substantially, or if your ‘retirement’ income is greater than your peak earning years. The possibility of higher future tax rates is a commonly cited reason for choosing the Roth; it’s risk aversion for the unknown. I address this possibility in a section below, but first an example illustrating with numbers.

Example With Median Earning Family

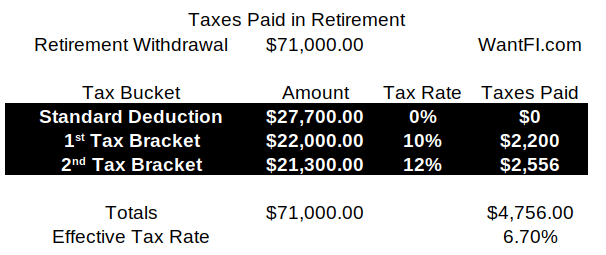

Let’s say you are a median working family in America earning $71,000 annually and taking the standard deduction (and ignoring credits for children, etc., which will drop your adjusted income further).

Most financial advisors will advise that you aim to have enough funds in retirement to withdraw 80% of your working year salary. But to make it a fair comparison, let’s say you did well with your saving and investing and have enough to withdraw exactly 100% of your working salary every year, the whole $71,000 enchilada.

Tax brackets are adjusted by inflation so you can ignore the effects of inflation here, or you can think about it in a simple two year period: your last working year and your first year of retirement.

At $71,000, your marginal federal income tax bracket will be 12% today, which means every $10,000 yearly contribution to a traditional 401k will save you $1,200 in taxes today right off the top.

When you retire and you are not working, you will start living off your regular 401k and those distributions will be classified as ordinary income. A portion of that money will be tax free due to the standard deduction, then a portion will be subject to the lowest tax bracket, and the next portion will apply to the next highest tax bracket and so on. The key point to recognize is that the taxes you will pay in the future will have an effective rate lower than the marginal rate you saved it at.

The table below shows that you first subtract the standard deduction (2023) of $27,700 per family (halve everything for singles). That leaves $43,300 of taxable income. The first $22,000 is taxed at 10%, and the balance of $21,300 is taxed at 12%.

If you chose the Roth, you would pay 12% up front every year, but by choosing the traditional account you pay slightly more than half that at 6.7%.

In this median case you can save 44% in taxes by choosing a traditional, standard retirement account.

When is the Traditional IRA / 401(k) equal to a Roth?

If you are married and combined earn $49,700 or less in 2023, this puts you into the lowest tax bracket after the standard deduction, and then both accounts will pay the same amount of taxes, ceteris paribus, and there is no tax arbitrage (if you have kids, you will need to account for child tax credits as well).

But again, you can still defer paying the tax twenty or thirty years later which can still be a benefit if you need the extra money today.

PRO-TIP: If you are US based, trade cryptocurrency and want to avoid the tax hassle see the Alto Crypto IRA. They support 150+ coins, there are no monthly or annual fees, no LLC setup fees, no processing fees, and they charge only 1% on each trade. Any cash waiting in your account is insured by the FDIC.

When is the Roth IRA better?

When your standard deductions wipes out your taxable income and sets your marginal tax rate to 0%. Then go all in on the Roth.

You can use your traditional 401(k) contribution to reduce your MAGI to zero making this possible for more people (another assist from the traditional account!).

Common Roth Fear: What if Taxes Increase?

The most commonly cited reason for choosing a Roth account is the risk that tax rates will increase in the future because of the national debt, or taxes just being low by historical standards.

Future tax rates are hard to forecast because its an extremely political decision that both parties are diametrical on. Taxes have been decreasing in the United States for decades now, so if someone chose a Roth account out of fear back when the Roth style was introduced in 1997, they left a lot of money on the table.

It’s impossible to know what congress has in store for future generations, but you can get a pretty good idea for the next 4-8 years by observing which party is in power, since tax rates only change with presidential cycles.

But let’s really push the limits on what could happen.

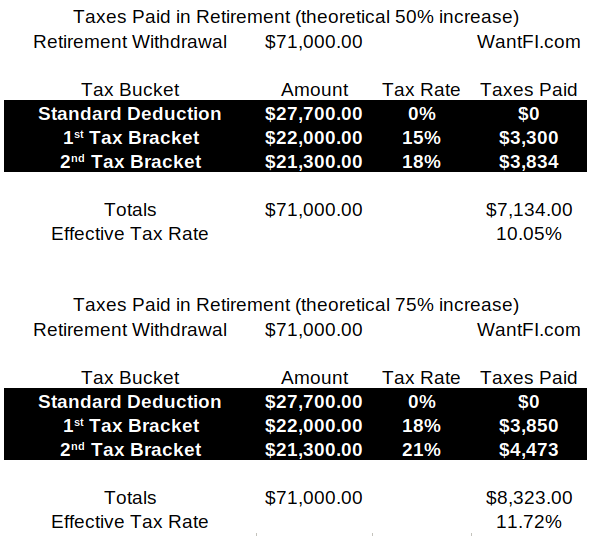

What if the income tax rates were to increase during retirement?

There are two parts to tax increases and usually both move when a change is made: the rates and how wide the brackets are. If the width of the brackets increase (they automatically increase over time due to inflation), it just means more money is taxed at lower rates before hitting the next marginal tax rate, and since we are trying to challenge the traditional account type, we will just assume that the width of the tax brackets stays the same for the analysis.

Furthermore, if tax rates were to increase during your working years it would only strengthen the case for the traditional IRA or 401k since you would be deducting at a higher marginal rate today.

But what about that worst case scenario where they increase right after you’ve retired? Would it have been a mistake to have not picked the Roth?

Below I show two scenarios where the taxes increase 50% and 75% while keeping the width of the brackets the same and show that using the traditional IRA leads to a lower effective tax rate.

Additionally, if tax rates were to double the day after you retired, then your effective rate would be a little higher at 13.7%, but of course this still assumes you are taking out the exact same amount of money in retirement as when you were saving (which is less likely since you should usually have lower expenses) and you are not using tax optimization to use a combination of retirement accounts and regular accounts to fund your lifestyle).

I want to point out that this would be a highly unrealistic scenario. The US government wouldn’t just pass a bill one day and double rates for everyone; they would gradually increase them over many years, and your contributions would benefit from the higher deductions along the way. I am just trying to show how unlikely it is for a Roth 401(k) account to outperform a Traditional 401(k) based on the common fear of taxes increasing in the future.

Risk: What if tax laws change unfavorably against the Roth?

Another point to consider is that with a traditional account, you get to take a tax deduction this year. It’s money in your pocket and it’s locked in. You know how much it is and there are no take-backs.

With a Roth you are betting that the future government, the one racking up trillions in debt every year, won’t look for a way to squeeze out more revenue and start changing the rules. There’s no guarantee that investment gains from a Roth will be tax free in the future.

What are the Disadvantages of a Roth IRA / 401(k)?

So not only will you pay a higher effective tax rate if you choose a Roth account as we showed above, you will also pay state taxes today if you live in 1 of the 42 states that has a state income tax. Of course, this really only factors in if you plan on moving to a state without a state income tax (or a lower average rate state) when you retire.

It can get a little complicated though. Some states, like Pennsylvania, tax your contributions regardless of account type, but don’t tax distributions during retirement. Most other states treat contributions and withdrawals the same way the federal tax code does, but there are some exceptions to the rules and you should double check your state’s retirement contribution handling.

For instance, Massachusetts doesn’t tax contributions into the regular 401k, but does tax deductible IRA contributions (thanks to reader Adam for pointing this out). It makes no sense, but these kinds of state nuances is what makes the Roth or traditional IRA / 401k decision difficult and hard to prescribe a one-size-fits-all.

However, if you live in a state that follows the federal method and plan on retiring to a state with lower or no state income taxes, this decision strongly favors the traditional retirement account since you’ll be saving both the marginal federal rate and the state rate on top of it, which is usually an extra 5% or more.

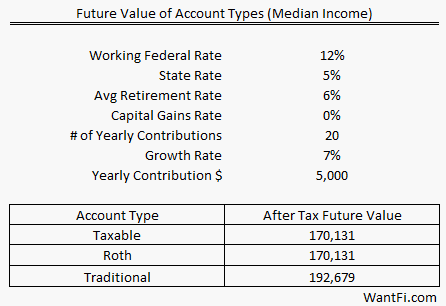

Median Income Family Example

To illustrate the complete picture, say your family earns $71,000, makes 20 years of contributions of $5,000, invested in index funds and earns a conservative 7% a year. Your state tax is 5% but you will move to Florida in retirement and have no state income tax. The following table shows the value of each account type, after tax.

The capital gains rate is 0% for families who earn under $89,250 a year (in 2023), which is an extremely valuable benefit and is why the taxable account and the Roth account are equal in this scenario.

How much retirement income will you have in retirement? If your taxable withdrawals are under the limit, you’ll still benefit (assuming existence then, of course)

But the results are remarkable, at the end of the 20 years, the after-tax value of the traditional account will be worth 13% more than the Roth or taxable account and that is all based on the tax arbitrage savings.

Let’s push the limits with a higher income family example.

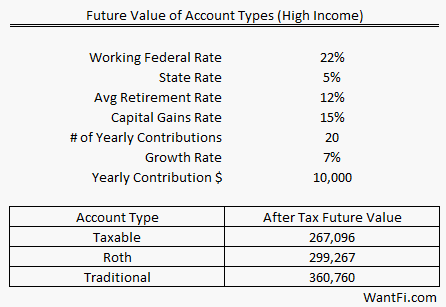

Higher Income Family Example

For a higher income family where the 22% tax bracket applies, and a 15% federal capital gains tax rate applies with a $10,000 yearly contribution, the Roth is worth 12% more than the taxable account, after-tax, and the traditional account is worth 20% more than the Roth, after-tax. That’s a full $60,000 more!

Again, the value of the traditional retirement account is hard to beat.

What Are The Advantages of a Roth IRA?

Other Roth Benefits

Roth accounts do have some other advantages, such as a lack of required minimum distributions (RMDs) in retirement (the Secure Act 2.0 lessens this already minor issue by raising the age to 75), being able to withdrawal contributions for specific purposes without penalty (nice to have, but you shouldn’t be using retirement funds), and income that doesn’t count towards Medicare Plan B payments (a minor surcharge).

When you stack these all up, you find they are don’t skew the analysis away from the biggest expense which is the tax you actually pay. Head to the comments below to understand why RMDs, Medicare Plan B and Social Security issues don’t change the result for most people.

My conclusion is the same, the traditional account style wins.

The Roth Has an Effectively Larger Contribution

One subtle benefit of the Roth is that even though both the traditional and Roth accounts have the same limits you can contribute to them, since the funds for paying the taxes on the Roth comes from outside the retirement account, the Roth account technically allows for greater retirement contributions, since part of the traditional account is earmarked for future taxes.

But don’t pretend that the taxes you have to pay today are not a real cost. They are. If you contribute $19,500 to a Roth 401(k) today you will have to pay an extra $4,290 in taxes today, so your equivalent traditional 401(k) contribution is $15,210 ($19,500 – $4,290). Or another way to look at the traditional account is that the federal government is loaning you part of your retirement funds for a 0% interest rate up to 30 or 40 years.

The fact is not changed that you are paying a high tax today instead of a low tax tomorrow with a Roth. Moreover, your future tax rate might be zero if that bracket still exists in the future and you employ tax planning strategy for keeping under that tax bracket when you limit your withdrawals effectively.

When To Contribute To a Traditional IRA / 401(k)?

If you are saving for retirement and you make enough income to pay over 0% in capital gains, you should use a tax advantaged account because Uncle Sam takes a cut on both ends: first when you earn it, and second when you grow it. The whole pre-tax vs Roth discussion is moot if you decide not to use a retirement account at all.

But the overriding conclusion from the analysis is that most people will have more money in retirement if they first maximize their traditional 401k’s and IRA’s before considering Roth.

You should consider Roth accounts only after you’ve maximized your traditional accounts. If you are a high income earner and are above the traditional IRA income limits, first maximize your traditional 401k and then maximize your Roth IRA account. And if you are above the income limit for the Roth IRA account, consider a backdoor Roth conversion by first contributing after-tax money to a traditional IRA and then immediately converting it to a Roth. You are paying the tax dollars anyway in this situation, so at least you can save on the back end with the backdoor IRA Roth option.

Final Thoughts

This article puts some analysis to the Roth vs traditional IRA / 401k decision instead of just making assumptions that not paying taxes in the future is the preferable route.

Future tax rates are uncertain, but even penalizing assumptions show that the traditional 401(k) or IRA outperforms the Roth because you are banking a tax savings today.

The Roth can be beneficial to the lowest income earners whose earnings don’t spill over into the second tax bracket, however.

Are you interested in learning about another tax favorable investment structure that has a deferred tax feature like a retirement account? It’s the high-yielding Master Limited Partnership (MLP). In that article, I show that the hassle of the K-1 tax form is actually worth the benefits the structure provides.

Drop into the Telegram chat room and read the lengthy comment discussion below.

Free Investing Tools

For advanced traders who want direct access to exchanges without “payment for order flow” shenanigans choose Interactive Brokers.

I use Axos Bank for its no-fee business account with free bill pay.